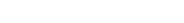

Chennai Day Zero: A Warning of Worsening Water Woes

Home to some 10.5 million residents, the City of Chennai off the coast of Bengal Bay in southeastern India is currently facing its worst water crisis yet, dubbed as Day Zero.[1] The coastal city is the first to fall victim to day zero as its four main water reservoirs have gone dry.[2]

This disaster came after prolonged droughts almost brought Mexico City, São Paulo, and Cape Town very close to day zero.[3][4] First coined in Cape Town, day zero is when the piped water supply has completely run out.[5]

Chennai’s Current Crisis Situation

Anywhere in Chennai, thousands of residents are seen lining up for hours with their containers for a meager water ration. Businesses such as hotels and restaurants are shutting down, while some workers from the IT sector are advised to work from home.[2] Even critical emergency facilities, such as hospitals and fire stations, have not been spared from the strict water rationing.[6][7]

Meanwhile, supply from towns with water to spare is brought to the city in water tank trucks. The authorities have promised to bring water at 10 million liters a day (MLD) by train, from a town 135 miles away, for the next six months. [8] This water ferry should support about 1 percent of the city’s 830 MLD water requirement.

Residents Exploring Solutions

The crisis is inspiring unique innovations. Recently, the Cape Town drought in South Africa has paved the way to the development of a solar desalination system, a technology that can be upscaled in other water-stressed areas near coastal waters.

In the parched City of Chennai, there is no shortage of homegrown solutions as well.

An apartment complex of 56 families in the locality of Sholinganallur set up a rainwater harvesting system. Four catchment areas were built in the complex; three of which directs rainwater in 3,000 L tanks to allow suspended particles to settle, while the remainder directs the rainwater to soak pits to recharge groundwater. The water from the three tanks is sent to a 100,000 L sump for storage which then goes to a treatment plant preparing it for distribution.[9][10]

Environmental Foundation of India, meanwhile, is leading the eco-restoration of numerous water ponds in Chennai with the help of residents volunteering to the projects.[11]

These projects are just few examples of climate resilience strategies that can be adopted in a larger scale to help developing urban areas absorb the impacts of climate change. It has also shown that cooperation between the people has the power to get ideas into fruition and overcome challenges of the changing climate.

Water crisis is one of the challenges we are facing globally and is listed among the Top 10 Risks in the 2019 Global Risks Report by the World Economic Forum.[12] Since the 1980s, water demand worldwide has been increasing by 1% per year and will continue to increase at a similar rate until 2050, pushing an increase of 20 to 30% compared to current water demands. [13] With this, the Chennai Crisis should be a wake-up call to immediately drive plans for an effective water governance and stronger stakeholder engagement which will help fend off an impending regional and global water crisis.[14]

References

- UN. (2018). The World’s Cities in 2018: Data Booklet [United Nations (Ser. A), Population and Vital Statistics Report]. Retrieved from https://www.un-ilibrary.org/

- (2019, June 18). Chennai water crisis: City’s reservoirs run dry. British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/

- Gerberg, J. (2015, October 13). A Megacity Without Water: São Paulo’s Drought. Time. Retrieved from https://time.com/

- Baker, A. (2018, January 15). Cape Town Is 90 Days Away From Running Out of Water. Time. Retrieved from https://time.com/

- de Lille, P. (2017, November 15). Day Zero: when is it, what is it, and how can we avoid it? Retrieved from https://www.capetown.gov.za/

- Narayan, P. (2019, May 17). Water-starved, hospitals in critical care in Chennai. The Times of India. Retrieved from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/

- Omjasvin, M.D. (2019, June 29). Water crisis hits fire service as firemen made to wait longer to fill tankers. The New Indian Express. https://www.newindianexpress.com/

- Shekhar, L. (2019, July 15). How exactly will water from the Jolarpettai train reach your taps? Citizen Matters. Retrieved from https://chennai.citizenmatters.in/

- Stalin, J.S.D. (2019). In Chennai, A Community Harvests 25,000 Litres of Rain Water In An Hour. NDTV. Retrieved from https://www.ndtv.com/

- Priya, L. (2018). Chennai Residents Nail Rainwater Harvesting, Collect 1,00,000 Litres Over 3 Hours!. The Better India. Retrieved from https://www.thebetterindia.com/

- Environmental Foundation of India. (2019, June 11). Innovation at Chennai’s Suburban Pond. Retrieved from https://efiblog.org/

- World Economic Forum. (2019). The Global Risks Report 2019. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-risks-report-2019

- UNESCO World Water Assessment Programme. (2019). The United Nations World Water Development Report 2019: Leaving No One Behind. Paris, UNESCO. Retrieved from https://www.unwater.org/publications/world-water-development-report-2019/

- Megdal, S., Eden, S., & Shamir, E. (2017). Water Governance, Stakeholder Engagement, and Sustainable Water Resources Management. Water, (9)190. Basel: MDPI. doi:10.3390/w9030190

- Most Viewed Blog Articles (5)

- Company News (285)

- Emerging Technologies (64)

- Microbiology and Life Science News (93)

- Water and Fluid Separation News (97)

- Filtration Resources (93)

- Product News (19)

![Join Sterlitech at BIO 2024 [Booth #5558]: Exploring the Future of Biotechnology](https://www.sterlitech.com/media/blog/cache/300x200/magefan_blog/b4.jpeg)